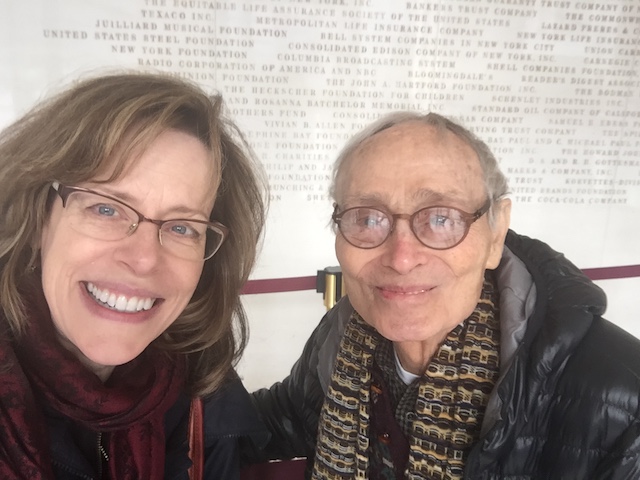

Carol: Gildo, if I am not mistaken, you win the prize for the longest tenure of an assistant conductor at the Met. Is that right?

Gildo: Well yes, I think probably that’s right. I started at the old Met in 1963 at 39th and Broadway and then moved to the new house along with everyone else. I guess it was a total of 55 years, 39 of them full time. I did retire a few times but always came back!

C: Tell me, how did you get the job? I know you started in Chicago where you grew up, but how did you get the job at the Met?

G: Well, I was a dancer in The Unsinkable Molly Brown and one night a dancer colleague of mine, Carl Davis, and I were talking before the show. You know, I started as a pianist, then became a ballet pianist, and then people told me to take dance classes to become a better ballet pianist – so then I naturally started dancing but only when I was older, around 16 or 17. Anyway, Carl and I were talking before the show. I was by then in my 30’s I guess, and I was wondering how much longer I could dance. That’s when he suggested I should write to the Met to see whether I could get a job there because I was a trained musician.

C: As a repetiteur?

G: I was actually thinking about applying as an Assistant Director! I lived in Germany for a number of years, so my German was not bad and of course I speak Italian. My parents were Italian and spoke no English when I was growing up. So, I thought I could do that job. I wrote to Francis Robinson who passed my letter on to Robert Herman - the son of the famous baseball player. I know you are a Yankees fan.

C: He was the son of Babe Herman?

G: Yes!

C: Oh my gosh!

G: I guess the letter was passed on to George Schick and he contacted me for an audition.

C: What was that audition like?

G: George Schick and Maestro Corsi both interviewed me and then I had to play and sight-read.

C: What did they give you to sight-read?

G: The big fight scene from Die Meistersinger and some bel canto.

C: When I was doing my research in the archives I saw you started as an apprentice.

G: Yes, Millard Altman and I worked for three years as apprentices. He still lives in NYC on the Upper West Side.

C: Yes, I heard that, I hope to interview him as well.

G: Oh, that’s great! He and I were trained by Maestro Corsi, the Maestro di Palcoscenico.

C: What was he like? How did things work back then at the first Met?

G: Maestro Corsi was very good at his job and really strict and formal. He insisted on everything being cued and conducted by memory. He didn’t allow any scores backstage. Also you know, it was a different system. ALL backstage cues, music and entrances were assigned by him, whether they were cues for the chorus or soloists or bandas. All the buttafuori work was done by us as well but he was in charge of everything. Now all that work is divided up much more. At any rate, Millard and I were trained for three years before we could do anything really. That’s how you learned the jobs back then, not at conservatories.

C: What was your first opera?

G: The Magic Flute- that beautiful Marc Chagall production.

C: I have lists of Assistant Conductors from my research in the archive department. Tell me about some of them.

G: I had several older colleagues who were really wonderful, like Jan Behr. He was so good-natured and warm-hearted and terrific at his job. He took me under his wing and was actually instrumental in assigning me my first backstage responsibilities. He was a Holocaust survivor and one day when we were at Bickford’s across the street (the first Met didn’t have a cafeteria) his shirt sleeve was undone and I saw for the first time the number on his arm. I didn’t know if I should say anything, but then I did just ask him about it and he told me his story. He was a wonderful person who had lived through an ordeal we can’t imagine now.

C: In the archive department I found so many things from those war years. Some names had asterisks beside them - for example, Peter Paul Fuchs * 1943/44 and 1944/45: US Army. He has such an interesting story. I think I also saw a singer who was listed as gone for the season because they were a prisoner of war!

Then there was Julius Burger who worked at the Met in the mid 1920s, went back to Europe and miraculously came back after the rise of Hitler with his wife, then worked again at the Met from the late 1940s until 1969. It is so interesting to remember that these assistants were by and large also established composers, not just conductors and pianists. Did you know him?

G: Yes, I knew him, a great man. There were so many incredible people. I was lucky to know them. There were also some great prompters I worked with like Adriano Petronio and Victor Trucco. He died while we were on one of our domestic tours, in the hotel room next to mine. I think he was only in his 50’s. I was devastated over his death, he had been such a great mentor. He really saw how green I was and taught me so much.

C: Did you work with Otello Ceroni? He was a legendary prompter.

G: No, he was just before my time.

C: Oh, that’s right. I see he worked only at the Met until around 1960.

G: Of course there were also terrific pianists and coaches.

I remember so well Alberta Masiello, the Italian mezzo and pianist. One day she played part of Falstaff and we just about fell over. The intricate detailing and everything she added was incredible. I remember Louise Sherman and of course Walter Taussig the famous coach who was such good friends with Karl Böhm. I also remember Thomas Martin sitting at the long table in our staff room working on his translations.

C: Speaking of conductors, who were your favorites?

G: OH! Patanè! Patanè had the most amazing stick technique you have ever seen. For example, there is a section in the Aida ballet where sections of the orchestra follow each other from top to bottom. I always made a point to watch the monitor to see how his baton kind of danced through that section. It’s hard to explain but it was so good. He knew everything by memory including rehearsal numbers.

C: Like Marco Armiliato.

G: Yes, exactly. He was also one of my favorites because he asked me to leave the Met and become his assistant!

(Laughter)

G: I truly loved Nello Santi as well — he was possibly my favorite. But then there were others.

C: Did you ever work with von Karajan?

G: Oh yes, what an amazing musician! One day we were rehearsing Das Rheingold- he always conducted from memory. But I saw what I thought was a score in front of him and I wondered why. I crept up a bit behind him and saw a pilot manual on his stand! I understand he did that quite often, conducting something from memory while studying something else. I tried to creep away but suddenly I got my foot caught in a slat between the floor boards (we were rehearsing on stage right) and couldn’t get my foot out. Everybody was trying to help me with my foot. He turned around and calmly said: But you have a boot with a zipper, why not just undo the zipper? I felt like such an idiot. He was conducting from memory with a pilot manual PLUS helping me with my boot!

C: There are so many great conductors you worked with!

G: That’s right! Kubelik was the music director for a time. He had a sensitivity which was so evident in his music making but also in the way he treated his colleagues and staff. Böhm was also fantastic to watch. There was seemingly no technique. He was quite old when I saw him work so he was always seated when he conducted. It always amazed me that the orchestra could read him. I loved watching him conduct the opening of Elektra. He just sort of threw his arms forward and raised about an inch off his chair and the first statement was perfectly together. How did he do that?

C: Did you always get to see them in piano rehearsals?

G: Oh yes, they were there – von Karajan, yes! All, or most of them.

C: Any others you want to talk about?

G: I was so lucky really. I remember one night talking with the chorus master David Stivender. He and I were backstage watching the monitor and discussing that night’s conductor. We heard a voice behind us: “Guys, I am making my debut here next week. Are you going to be talking about me then?” Well, that was the young James Levine! I was able to work with him for a long time. One night during an Aida I had made a big mistake with the banda. I was personally devastated and just wrecked about it. I went down to the pit level at the end of the show to apologize to him when he came out of the pit. He probably saw my face, you know, I was just humiliated. He looked at me and said: “Gildo, how many performances have you done that have been great?Are you going to beat yourself up for one mistake?” He is one of the greats.

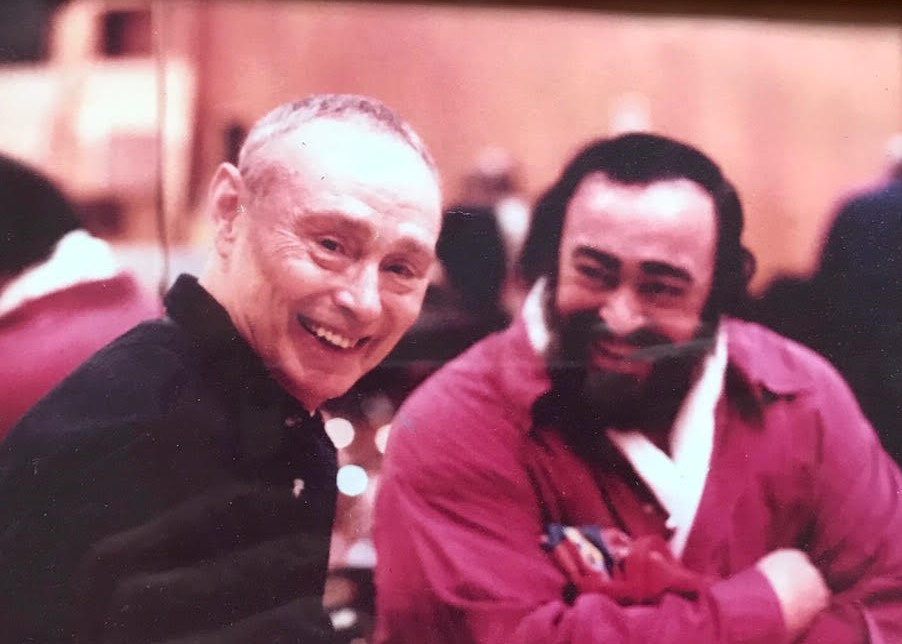

C: Gildo, you were Luciano Pavarotti’s coach for so long and were such good friends. Tell me about that. How did you meet?

G: How did we meet? When he made his debut in La boheme. I later told him if he had sung that well when he was sick (he had to cancel almost the whole run because he was sick) what must it be like when he feels good? Well - we found out! Our first real collaboration was Turandot. Yes, I guess I was the first person to hear his “Nessun dorma”. We studied all of this during the domestic tour with the Met. He would sing his performance of La fille du regiment. Then the next day before he left town we would study. After our study he would have to check out of the hotel, so I would go with him to the front desk because those clerks couldn’t always understand him. I remember in one city, he presented his American Express card and the clerk asked him for identification. The irony was that he was on all the American Express commercials at that time and they were airing constantly!

After he made the Turandot recording with Zubin Mehta, Decca Records wanted a coach to work with him every summer at his summer home in Pesaro. This was always to work on his next album. And so started our summer study sessions. That went on for about 17 or 18 years. My favorite person there was Signora Anna, custode and cook. Her cooking was sublime - only one problem - she spoiled me. Now when I’m having one of her specialties I think “Oh Anna, how I wish you were here”.

I asked Luciano where he got her to cook for him and he said the Catholic priests have the best cooks so he stole her away, I believe, from a Neapolitan monastery. He was very good at bringing people to him whom he loved and trusted. He brought an Irish nurse named Mary from NYC to nurse him when he was ill.

The only problem with our summer study session was that he never wanted to study! For instance, during a lesson those divine smells coming from the kitchen would distract him and he would have to go investigate. He would come back with two slices of homemade bread and the best marinara sauce you have ever tasted. Another diversion tactic was to offer me a glass of ice cold bubbly Lambrusco. On a hot Italian afternoon how could I resist? Then there’s a second and a third: Addio lezione!

Now a footnote about Lambrusco, Luciano always said it didn’t travel well. He was right because I would buy some in NYC and it was never the same as it was in Pesaro. I miss Luciano - and the great food and drink and experiences. This photo is of us in Pesaro - he always got me to paint. Another diversion tactic!

C: What about sopranos?

G: Oh, Birgit Nilsson! Those “ho jo to ho’s” would pin me to the wall backstage! That SOUND!

C: I think, Gildo, you are one of the people at the Met who have held the most varied positions. You started as apprentice, then Maestro di Palcoscenico, pianist, coach (I see in the archives you played plenty of recitativo performances in the pit) and then finally as a diction coach until your final retirement. Can we talk about how technology has changed from the Met at 39th and Broadway to the present day? We always hear about how they would have to poke holes in the scrims or the set walls in order to see the conductor to sync the orchestra up with the backstage music.

G: Yes, that’s right. That happened. But there was also a different system. There was a person ‘playing’ or rather, beating on a type of keyboard at the same tempo of the conductor. They would be near the stage manager so they could hear the orchestra and they would look through a peephole as well. It was transmitted to a light system with numbers to help backstage. It’s hard to explain the system. But the bad news is while we were way at the back ready to start there would be NO indication of any kind of up-beat during any section and worse - we had no idea when anything would start! There was no preparation, suddenly there was number one!

C: It sounds similar to the system they apparently used in Bayreuth, where an assistant would sit at the back of a string section and tap out the beat – and this would be transmitted through a type of cable system backstage.

G: It sounds similar, yes.

C: I know rear view mirrors were swiveled out backwards in the prompt box before there were cameras pointed at the conductor?

G: Yes, but even after cameras were used at our theater we would have to take those mirrors on domestic tours because not all theaters had the new cameras that we needed.

C: What about rehearsal spaces at the first Met? What were rooms and spaces like?

G: Well, of course everything was smaller. But I loved that old building and the theater itself was gorgeous. There was less storage; it was not easy to move sets around or to store them. Today of course, with elevators and lifts and all the storage trucks outside there is much more ease and ability to change out a show.

We had one big rehearsal room at the top of the opera house called “roof stage” and some smaller rooms. I remember everyone making a bee-line to the roof stage if there was a famous conductor about to start an important rehearsal. We would make a mad dash! I remember Bernstein’s first rehearsal for Falstaff for example.

We had some smaller rooms as well to rehearse and coach, but today at the Met there are two very big rehearsal rooms as well as the theater itself and some smaller rooms. You know we also used the Italian tradition, using the street names to indicate “stage left” or “stage right” – we would say 39th St or 40th St.

C: Gildo, I remember you and I having a blast on the last Japan tour. We had some fun! Can you tell me any stories about those legendary domestic tours?

G: Sure! Well, I do remember every time we would enter a new city the train would have to divide in two in order not to overwhelm the station in the new city. The back part of the train would just sit on the tracks and wait for the first part of the train to unload before it was pulled into the station. People could then disembark easily and efficiently.

My compartment was in the front of the train but one morning I was at the back of the train in a different compartment (for some reason or other!!!) and when the back of the train finally pulled into the station there was the company manager standing on the platform with my luggage shaking his head.

(Laughter)

C: What an incredible career you have had, Gildo. I could sit here talking to you forever. A pianist, a dancer - we didn’t even talk about Bye Bye Birdie and your movie career! You were in the army all over the world, had multiple jobs and a wealth of friends and colleagues. Plus, you are turning 90 on August 8, 2020.

G: That’s right!

C: I will make you a big chocolate birthday cake, your favorite. Do you remember my chocolate cake?

G: Oh yes!!!

C: Thank you Gildo Di Nunzio – we are so grateful for sharing your memories with us. Happy Birthday!