CI: Here is what I will call a "rapid round”… Who are your favorite singers and why?

JK: Alfredo Kraus… incredible singer, gentleman, intelligent, always prepared, always on time, always kind to colleagues. There are many others. He came to mind first. I worked with him a lot.

RM: For me, Carlo Bergonzi comes to mind, not just because he was a truly great singer, but also because, as I mentioned, I played for him in Italy for many years and he was a mentor. There are many, but we could be here for hours.

CI: Who are you favorite conductors and why?

JK: James Levine, Carlo Maria Giulini. Levine knows singers well, supports them, leads them but is with them, knows how to work with them so they improve. The orchestra sounds glorious with him conducting. Giulini I only worked with once, but I was in Heaven for months afterward. He knew how to rehearse the orchestra, give nuance, was right with the singers. Both of these gentlemen worked with traditions and understood their importance. When a conductor excels, as these two (in my mind, anyway), then the entire performance is elevated to a level that is breathtaking. High praise was when they complimented me. I have never forgotten.

RM: That is a long list, but Thielemann, Barenboim and Rattle are at the top. Of course, James Levine, for all of the reasons Jane mentioned and because he believed in me and gave me my career. Working with Yannick Nézet-Séguin has also been a privilege and a pleasure.

CI: Who are your favorite directors and why?

JK: Zeffirelli.

RM: I agree, Jane, Franco Zeffirelli. Also for me, Jean Pierre Ponnelle was a director in a class by himself. He directed staging rehearsals like a great conductor with an orchestra and he always worked from a full score. Both of them were geniuses.

CI: NOW for the big one: Who is your favorite composer and why?

JK: Cannot say. I love them all…

RM: Amen, Jane!

CI: Can you each tell me how you started at the Met and how long you worked there? Do you have one favorite moment?

JK: The Met called, I went in for an interview, I was hired. I worked there more than twenty years.

RM: As I said, Maestro Levine hired me and the first thing I played for him was Rosenkavalier, I think in 1994. My last opera was Elektra in February of 2018. One favorite moment? Jimmy's Twenty Fifth Anniversary Concert, standing in the green room between Birgit Nilsson and Gwyneth Jones, everyone glued to the monitor as Jane Eaglen sang the Immolation Scene.

CI: And can you tell me about some of the older colleagues who might have worked there when you started out? Did you have anyone who mentored you or really helped you or someone you admired? I am so fascinated with all those lists I came across in the wonderful archive department there run by Peter Clark.

JK: I am still friends with Millard Altman, someone who retired from the Met long ago. Mentors were from other theaters and people like Nicola Rescigno, Roberto Benaglio (famous chorus master for whom I was assistant one season at Dallas Opera).

RM: Richard Woitach just passed away recently and he was such a huge talent. I think of people like him and Phillip Eisenberg and Walter Taussig. They were role models and I learned from all of them.

CI: Do you both have any advice to pianists today on how to start? How to study? What to study? How to practice that is different from being a solo pianist?

JK: Sight reading is imperative. I believe I listed above about how to study.

RM: I agree with Jane. I would also highly recommend the book, The Art of Accompanying and Coaching by Kurt Adler.

CI: Thank you both so much for your time, I miss you both tremendously and am so grateful know you both!

CI: Jane, where did you grow up and go to school? Do you come from a musical family, are there other siblings or family members who became musicians?

JK: I grew up in Illinois. In high school I studied piano at the Chicago Conservatory of Music, then privately with Rudolph Ganz for a short period of time. I attended University of Illinois where my piano teachers were Stanley Fletcher, Soulima Stravinsky and Malcolm Bilson. I had just started to work on accompanying/coaching with Paul Ulanowsky, then he died. John Wustman was then hired and I studied with him. Various summer studies included University of Salamanca, Spain and Leningrad University, former USSR… both for language, as well as AIMS in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany. My father played violin extremely well, though he did not have a career in music. Some of my fondest memories are of accompanying him. He had a wonderful ear and drew a fantastic sound from his violin. My mother played piano. One of my brothers had an incredible baritone voice and I accompanied him from grade school through college. My family environment promoted music, though not classical. I grew up playing a lot of Broadway music and popular songs my parents knew. At holidays and when company visited, entertainment was singing around the piano. At a very young age I took over playing these “events”. It was always great fun.

CI: And Bob, what about you? Tell me your family background and your schooling and teachers.

RM: I am from Seattle, but we moved several times while I was in High School. I spent my freshman year in Whittier, California, my sophomore year in Chicago and my last two years in High School in Indianapolis. I had piano teachers in Seattle and California. When we moved to Chicago, Mary Sauer became my real teacher and mentor. I continued to study with Mary at DePaul University in Chicago. I won a scholarship to the Aspen Music Festival when I was 18, where I studied with Aube Tzerko and I took some lessons with Lili Kraus. After graduating, I spent a summer in the Merola Program and afterwards, I moved to Milan, Italy. I also studied German at the Goethe Institute in Munich. I had one brother, eight years older than me. Nobody in my family was a musician, but some of my earliest memories are of my mom singing. In grade school, I became very close with a family that lived nearby and their piano bench was filled with music from the thirties and forties. That is where I learned to play a c major scale and I taught myself the bass clef. Treble clef I knew because I had started playing the clarinet. Also, I used to listen to the piano lessons of a friend in grade school and I would learn her pieces and play them on her piano.

CI: Do you have memories of your first piano lessons? Did you love it or was it sheer torture every Saturday morning?

JK: My Mom tried to teach me piano when I was four years old, but soon took me to my first teacher, Mrs. Sweetman. She used to play organ for silent films in movie theaters. I remember the wall in her waiting area had musical notes on it. Lessons were often in the evening and were about half an hour from our house. When my Dad took me, he would frequently take me to Snackville Junction afterward to get a hot dog that was delivered on a train car that ran around the restaurant. But I digress. Mrs. Sweetman did not teach the classics, but taught how to improvise, roll chords, etc. Classical piano music came in high school when my parents found me a different teacher. After that teacher I went to Rudolph Ganz before going to college.

You asked if I hated the lessons. No, I did not. I do remember a few years after I started studying with Mrs. Sweetman I wanted to quit and study marimba. My Mom said I could if I told Mrs. Sweetman I was quitting. Frankly, I was scared of Mrs. Sweetman so I never quit. THANK THE LORD!!

RM: The marimba? I love that , Jane. We did not even have a piano until I was eleven. I was obsessed with the piano and , when I finally did have my own instrument and teacher, I lived for my lessons. I only studied for a year before we moved to California, but by the end of that time, I had convinced my teacher to let me play the Chopin's A flat Polonaise, which I performed with great bravado and absolutely no idea what I was doing.

CI: Teaching is really an incredible art - a real gift; and the difference between traditional Western teaching and Eastern teaching is significant. I always think having an individual, private music teacher is something much closer to the guru system than the Western tradition of teaching. The student ends up not only having reverence for their teacher but wanting to BE the teacher and EMULATE them in every way. Did you both have teachers like that? Tell me about them and how you think that manifests itself in the musical relationship.

CI: Do you remember how you made the transition from being a solo music and chamber music pianist to becoming a repetiteur? What are your recollections of this process?

JK: Do you remember the brother I mentioned who was a baritone? I always accompanied him growing up and then in college. We would perform places even while in grade school. I played solo, but I accompanied more than anything. I could sight read anything dropped in front of me and accompanying was just “in me”, so to speak. I always felt joined with the singer or the instrumentalist. When I finished my Master's degree, accompanying was what I wanted to do so I moved to New York. I did not find work recital accompanying but I found work in...opera. Through grade school I had earned a little money accompanying instrumental contestants; in high school I accompanied singers; in college singers hired me to teach them music. This was all just in me from having grown up with my brother, I believe. Some of my first opera jobs in NY were with Bel Canto Opera on the lower East Side. There the pianist coached all of the cast and conducted the performance from the piano. It seemed natural to me. I even got a review in Opera News for one of those operas. Since I accompanied my brother from grade school on, working with singers, teaching them, had become second nature to me.

RM: I played in many voice studios in Chicago, sight reading, making some extra money and learning about singing technique. A High School teacher in California had shared her love of opera with me and we would talk about the Saturday Afternoon Broadcasts from the Met. I started collecting complete opera recordings and I knew much of the standard operatic repertoire from listening to these recordings all of the time, so I was already hooked. I mentioned Maestro Favario, who prepared me for my Merola audition. My summer there was a big turning point.

CI: I remember learning my first few operas and it just took me forever. I had no system, no training and had no clue how to go about this. Do you remember those first few operas?

JK: In college I wanted to put on an opera myself without orchestra. Of course the singers were game for it. I used a converted railroad station; Puccini's La Rondine was the opera. I taught all the singers the roles. La Favorita and The Crucible were probably the next two full operas I learned and they were for Bel Canto on the lower East Side of New York. I remember the director for The Crucible contacted Robert Ward to ask if he would attend a performance. He could not, but he offered to meet with all of us one evening, which we did. It was an incredible evening and one I will never forget. Since I grew up accompanying my brother (remember the baritone?) I learned at a very early age how to sing along in my head. This was the start of being able to sing all the roles while playing the piano, I believe.

RM: I had done my best to prepare Cenerentola and Falstaff for my summer at Merola and I realized that my biggest problem was my spotty Italian. By the next year, I had moved to Milan, Italy and eventually became fluent. It all has to start from the language.

CI: Can you each describe the system you developed for actually learning the skills? For example, in what ORDER do you learn the scores? What comes first, what comes last? How much keyboard work vs desk work is there? How much listening to recordings? AND who taught you these skills?

JK: I translate first, read the libretti. I slowly play the part while singing. I learn each vocal part. Sometimes I need to slow way down, play just chords to find the melody if the opera is more complex harmonically. Eventually I can sing while playing and skip between lines. This is imperative, for a coach must be able to sing cues for the singer one is coaching. Also, learning this way has me at one with the score. By that I mean when a conductor or director calls out where he/she wants to start instead of calling an orchestral number, I know where it is because I learned the words so well. This is just the way I learn. No one taught me but I do teach this to my students (pianists) who want to work in opera.

RM: I approach if from every angle.The libretto, playing the part on the piano, orchestration, including all of the cues and dynamics missing from the reduction and deciding what needs to be put in. Listening to recordings and getting the color of the orchestration in my ear. Figuring out how it is probably going to be conducted and planning for all of the possible variables. Finally, being able to play and sing it. Every project is a little different. I had to learn Reimann's King Lear in just six weeks. I have had to learn some very difficult scores, but this was crazy. I was working at NYC Opera in the summer of 1985 and San Francisco Opera offered me a full time position for the Fall , with this opera to start the season. I had to study on my off time and I just lived, breathed and slept with that score. Fear of showing up unprepared should not be underestimated as a great motivator. Over time, you become better at these skills and you learn from experience what you need to do.

CI: Isn't it amazing how much of this job is STILL learning on the job, instead of at conservatories? Why is this so?

JK: I started a division in my summer program for pianists to work on opera and learn how to coach, conduct backstage. I have had several Danish pianists attend. After about three years, the Royal Academy in Denmark started such a program for pianists. I believe it is starting to take hold. Let's face it, though: some things cannot be taught. I had one such pianist. No matter how many times I told him to breathe with the singer, showed him how to do it, told him to sing the words in his head along with the singer, he just could not do it. I had him work on just the words, then add the piano without having a singer there. He still could not do it. Accompanying, coaching, prompting are all arts, and separate ones at that.

RM: That is so true, Jane. Each of those arts requires a very specialized expertise. Carol, you asked about learning on the job, and I think that one of the things that makes our work so fascinating is that you continue to grow and learn from all of the artists who cross your path.

CI: I know when I teach at various programs I always insist on having lessons or at least classes for pianists. If they say no to this, I usually just explain why I need to do this. They always listen, say yes, and are very happy with the end result. Do you think education for pianists in this area is changing?

JK: As I mentioned above… yes, I believe it is changing. Learning this in school cannot replace the experience of working in a theater, though.

RM: I think the level of talent is off the charts and the opportunities for training are better than ever. When I went back to teach at Merola, I was very impressed with the pianists I worked with.

CI: Jane, tell me how you started the Bel Canto program in Florence and how it still inspires you today.

JK: I am someone who firmly believes in traditions in opera. At the very least, I believe a singer, a coach, must learn them before deciding NOT to use them. They are integral to 19th and early 20th Century opera. That said... I was already working at the Met when I decided to start a summer program for individual coaching for singers and classes to teach what Italian traditions exist and how they came about. I decided to do this because I saw that traditions were fading away. They are handed down, so in person teaching is essential. I founded the non profit Bel Canto Institute in 1987, fundraised for three years, held the first summer program in 1990 on the campus of SUNY/New Paltz. Later I moved the program to Florence, Italy. I love singers and have always wanted the best for them. I firmly believe that traditions are not only important because they come from composers and the era of the composers, but because they also help singers. I did not want to see all of this gone forever, so I founded this program. The institute is in memory of Luigi Ricci. The youth division program is in memory of Luciano Pavarotti, whose wife gave her permission and blessing for this dedication.

CI: Bob, I always wanted to ask you all about your work in Bayreuth, I know you worked there for many seasons. Why did we never have a gab about this at the Met? I guess we were always so busy. Tell me about that now.

RM: I was invited to audition for Maestro Levine because he was looking for one more person to assist him at Bayreuth and my friend, John Fiore, had recommended me. We met in List Hall and I sang part ot the Immolation Scene and some other excerpts and he hired me. Rehearsals for the Ring began in the Spring and the Festspielhaus was freezing cold, I remember wearing gloves in between playing for stagings. We had a brilliant cast, including newcomers like Nina Stemme as Freia, Rene Pape as Fasolt and Falk Struckmann as Gunter. Can you imagine? Norbert Balatsch was the brilliant chorus master and Wolfgang Wagner was running the festival. Fairly early on in the rehearsal process, Maestro Levine asked me to play all of his piano rehearsals and it was because of our collaboration there that he offered me a full time contract at the Met. I did six seasons at Bayreuth, the rehearsal year and all five years of the Ring Cycle. I did everything from conducting backstage to playing anvils for Rheingold. The covered pit and acoustics are famous, but the only opera Wagner wrote for the theatre was Parsifal and hearing it there is a magical experience.

CI: What are your favorite things about each other when you work together? How has your relationship grown in this art form?

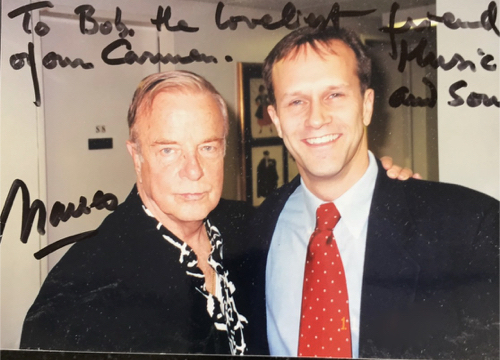

JK: I liked Bob from the moment we met. He is not at all self centered, but a natural, warm, kind person. Rehearsals were fun when he was there, for we would talk during breaks, smile across the piano. He has a great sense of humor which is important to me. In addition to the fabulous personal traits, Bob is an excellent pianist, musician and colleague. He never speaks ill of anyone. He has taught for me at Bel Canto Institute and the students love coaching with him. He treats them as if they were professionals, though some are teens. Kindness flows from my dear friend Bobby.

RM: My friend Jane! Well, she is brilliant and a consummate pro, always a positive presence in a rehearsal. When Jane invited me to the Bel Canto Institute, I was so impressed watching her coach singers, always smiling, always encouraging, yet insistent at the same time. Two things come to mind about Jane at the Met. In my first seasons there, whenever we were doing an Italian opera with Maestro Levine and a question arose about phrasing or an alternate version, he would turn to Jane and always take her advice. That is quite a compliment. Jane has a wonderful, dry sense of humor and we shared many laughs in rehearsals. I remember once we were rehearsing the first scene of Walküre with Debbie Voigt. In the Otto Schenk production, there are those huge caveman sized bowls that Sieglinde has to serve to Hunding and Siegmund. Debbie accidentally dropped one on the floor and Jane says, "Oh no! Her good earthenware!"

CI: Jane, how did you get started as a prompter? Do you think this is a skill anyone can learn and excel at? What are the skills you must have to be a good one and what kind of personality?

JK: I was working at Dallas Opera as Assistant Conductor and in charge of conducting back stage bands. The prompter there was Vasco Naldini, a very well known prompter whom Callas took with her to prompt her when he was not busy at La Scala. Nicola Rescigno was conductor/music director at Dallas Opera when I worked there. I watched Naldini and became friends with him. His one bit of advice was, "Know the score so well you can close it". Matinee performances at that time were a reduced version of the opera and they were often in English, though not always. Naldini did not prompt those. No one did. When I was at the piano, I would throw words if needed. That is basically how my prompting started. More and more I did that for the reduced versions if there was trouble. Then one year Naldini decided to retire. DCO hired another Italian to prompt who at the last minute said he did not prompt German. One of the operas for their season was Der Fliegende Holländer. DCO knew I know German so they called and asked if I would prompt it. I did. It opened another door for me and I soon went on to Chicago Lyric Opera as prompter, Falstaff with Giulini in Los Angeles, then the Met. I do believe there are certain skills one must have in order to prompt and not everyone has them. You must be well coordinated and able to juggle several things going on at once. I think of a prompter as three air traffic controllers in one. Nerves of steel are a must, as is an understanding personality. One must be able to calm singers, yet keep them on track during performances. The mind has to be quick enough to jump from one singer to another, one line to another, fix problems. The music never stops so speed of correction is imperative. One has to concentrate for long periods of time without losing focus. If a person has a “knack” for prompting, as I often call it, then some pointers can help. Flat out teaching it I do not think is possible. There is either a talent there for it or there isn't. Without that knack, flexibility, timing, one cannot prompt. One can try, but it will not be good. A bit of psychology is helpful. Singers’ jobs are terribly difficult so kindness, understanding and help are imperative. A smile goes a long way in helping a singer get through a performance. Languages are imperative. If not fluent in a language, a prompter must at least have a knowledge of the language and good pronunciation. A basic understanding of how difficult it is to sing is necessary, I feel. It is not easy.

I will tell you one quick story. When I was at university I wanted to study voice for a year to see what singers go through in learning. Mind you, I have no singing voice. I accompanied at university so the voice teachers all knew me and liked me, so I got to study for a year. It was SO hard that it took me until second semester just to be able to sustain a song. Now, remember my brother, the baritone? For a couple of years he also studied at U. of I. I was so excited about my vocal progress that I wanted him to hear me sing, so I asked him to come listen one evening. I had learned a Hugo Wolf song for the occasion and could just get through it. I felt proud that I did and when I finished, I asked, "Well, what do you think?" My brother looked at me and said, very calmly, "Jane, if I played piano like you sing, I would cut off my hands." At the time it was a blow. Shortly after I started laughing and have not stopped. You see, he was right. It was horrible. The point? I learned a LOT about what singers go through. Back to the topic. Like all prompters, I have some really funny stories, but I would be digressing again. (Remember Snackville Junction?)

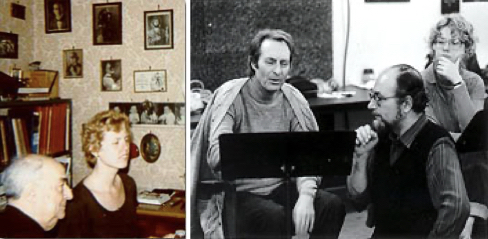

JK: I do love teaching and believe part of that love comes from having had excellent teachers myself. I could see the joy they found in teaching which I also found. Malcom Bilson was one like that. I started with him my freshman year in college and grew by leaps and bounds under his guidance. To me, how a teacher communicates is such a big part in how a student learns. I was the student who understood abstract terms Bilson would say as to color of chords, etc… When Bilson left U. of I. to go to Ithaca I studied with Stanley Fletcher. He was incredible in that he worked technique like Bilson never had. Again, I grew steadily. Both teachers were very supportive in every way. Luigi Ricci greatly influenced my life and career. I was working at Dallas Opera and told the administration I wanted to go study with him. They applied for a grant for me from NEA, which I received twice. That and another grant made study with Ricci in Rome possible. I studied with him three years and went back a couple of other times. We remained close until his death in the early 1980's.

RM: I could never repay the gift given to me by Mary Sauer, who was like my musical mom and mentor. She was not taking students when I played for her, but she agreed to work with me if I spent a year studying nothing but technique, Fritz Reiner had created a position for Mary as principal keyboard with the Chicago Symphony and she introduced me to a very high level of musicianship and excellence. She was a very busy working musician and she would take me to her orchestra rehearsals and concerto gigs and chamber music rehearsals with legendary principal players from the CSO, like Frank Miller. I remember sitting at her kitchen table when I was sixteen and she told me that she thought I could make a career as a pianist. She believed in me and she opened a door for me. I am forever grateful to her for that. Later, I received invaluable help from Giulio Favario, the chorus master at the Chicago Lyric Opera and from Carlo Bergonzi. I was at the piano next to Bergonzi for many winters in Busseto at the Accademia Verdiana.