H: How did opera come into your life?

J: Years after a lonely life of playing concert piano, my encounter with opera was a revelation. One day a friend asked me to drive her to New York for a voice lesson. A handsome and charming Ukrainian bass opened the door, Andy (Andrei) Dobriansky. With big Ukrainian vowels, he said: “You are the pianist. You are pretty.” He asked me what I knew about opera, and I said I didn't know anything. Andy took me to Madame La Puma’s tiny opera company. She was the mother of Alberta Masiello, who, following her singing career, became one of the pivotal coaches of the Metropolitan Opera. At La Puma’s I met Nico Castel, who taught me a lot about opera and encouraged me to go to Italy and study Italian. It was quite an adventure to go to Florence and stay there for a while.

The Metropolitan Opera hired Andrei and me for two years, working on four operas per year, touring all over the U.S. Risë Stevens, who oversaw the tour, told me I needed to change my clothes and hairdo. When I protested, she said: “We're not looking for comfy; we are looking for sophistication.” One day she said: “Today you will conduct the performance of La Traviata.” I had no idea how to conduct anything. “Well, you know the music very well. Just see that it goes.”

When we were back from the tour, a noted German coach who lived next door asked me if I wanted to go to New York City Opera for an audition. I was hired by Julius Rudel, who gave us tough love (“What do you mean you're in the hospital? All right, I'm going to pay for six weeks. Do not be sicker than that”). He had such a feel for many kinds of music, and I learned so much from him. One time, I had to play the gong backstage, and he almost chopped my head off afterwards: “Don’t you know you must warm it up before you play it?”

On the MET tour I met Clarice Carson, a soprano from Canada. We were all living in the same apartment on the Upper West Side, maybe six people sleeping on the floor. Work was scarce and no one had any money or a place to live. One day Clarice asked me to play an audition for her. Whom for? She did not really know. I was tired of playing for her auditions, and she really had to insist. We went to the Ansonia and auditioned for the brother of a soprano who was going to sing La Traviata and wanted a soprano for two of the performances in Barcelona’s Liceu. He was Carlos Caballé, Montserrat’s brother, who managed her career. He hired us both, and off we went to Spain.

I was oblivious of politics at the time, and this was Franco’s Spain. I did not know much about the tensions between Catalonia and Spain. I was amazed to see soldiers everywhere with guns. And my colleagues told me never to have more than two or three people in my room. When we did Don Carlo, soldiers came in and stopped the show. Verdi’s pieces were too political. We had to empty out the entire theater. Montserrat was nervous about that because her family was in a precarious situation. In the late 50s, her father was sent to jail and she and her brother had to flee to Germany. Following the Traviata, they asked me to stay for more productions, so for a few seasons I alternated between City Opera and the Liceu. We were all so poor. José Carreras and I were sleeping in the same hotel, and we were eating this delicious thing called pan tomate (bread with tomatoes and olive oil). That's all we could afford. But I gained a lot of knowledge and experience. Opera connected everything that I really loved: music, words, and theater.

Montserrat and I learned a lot of music together. She was really quick. We wound up sitting on the bathtub with the music in our laps because her father was watching TV in the living room and the children and the rest of the family were all over the apartment. It was such a warm and loving family. And one “fatal” day, she said, “Giovanna, I need you to prompt me tonight.” I said, “Monse, in the theater I work in we have no prompters. I have no idea what they do.” “You say the word a little before I'm saying it” was her reply. I went to one of the Italian conductors and he showed me what to do. I got in the little box. I think one of Montserrat’s kids was in there with me that night. That was the beginning of my prompting career. When I came back the second year, she said: “You are much better this year.” It was so interesting to be part of the performance. One night Giacomo Aragall, the tenor, fainted in the middle of a performance. The prompters at the Liceu had the key for the curtain, so I brought it down. One day we were in the north of Spain when Alfredo Kraus was singing Werther. Just as he was about to say he did not want to live anymore, there was a shot from outside. I panicked, not knowing if they had shot him or not, so I rang down the curtain. I looked under it, and he was motioning to me that he was okay and to bring the curtain back up. There were so many adventures in Spain and so many beautiful singers that came from all over. It was glorious, and I loved it.

Hemdi: What brought you to music?

Joan: I was born in Boston, to a mix of cultures: Italian, Irish, German, and Eastern European. I grew up on Long Island, in a Jewish-Christian home. I did not really know that there was a difference between the two. I still don’t. In school everyone was encouraged to play an instrument, and I was offered the violin. But I went with my uncle to Carnegie Hall to see Arthur Rubinstein and he was having such a glorious time playing this big instrument that I went home and told my mother I wanted a piano. The milkman knew where there was one for sale. It wasn't good-looking, but it was a good piano, a concert grand that I have to this day. My mother paid $300 for it; that was a lot of money then, about two weeks’ worth of meals.

In Hempstead High School, which was famous for its marching bands, I was assigned the glockenspiel (you cannot imagine how difficult it was to walk around with that heavy instrument). And then I received a scholarship from Hofstra College to study music.

At Hofstra I met Francis Ford Coppola, the film director, who was doing theater productions there. He said: “You have a scholarship, come and help us.” It was then that I discovered the theater. Even going to a movie was a novelty to me, but theater? One did not go to the theater. Whoever heard of it? He was very inspiring, and invited me to watch, and gave me the odd jobs. I was shy, and they helped me come out of my shell. When I graduated with honors, I taught music to young schoolchildren. But nobody ever taught me how to teach first-graders, or how to help the little boys when they needed to go to the bathroom. Some of them must be traumatized to this day. This job was clearly not for me.

H: What brought you to the MET?

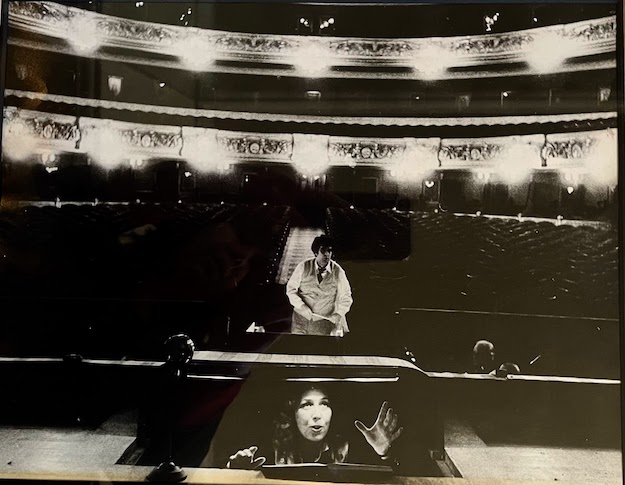

J: One day the phone rang. “Hi, Miss Dornemann, Maestro Levine would like to see you on Thursday at four o'clock.” I had been recommended to him, especially because I could do both prompting and coaching. My meeting with Levine included a conversation and an audition. I told him right away: “I can't play any Strauss for you, or any modern operas. That’s not the repertoire I know, and I'll go home if you don't mind.” I meant to say, “I'll go home if you mind,” but I was very nervous. Levine answered: “Well, there are quite a few letters here that say not bad things about you, so you must know something.” I told him all the repertoire that I knew, and he asked me to play and sing for him. My singing is horrible. I have the range of two steps. He said: “Joan, don't sing. You play very well.” So I played some more, and he played and I prompted, and we talked some more. It was a long hard audition. At the end he said: “I'm going to put myself in a lot of trouble. I should be hiring a man, but I'm not going to. I'm going to hire YOU.” They hadn’t had any women prompters before. The news hit the papers and all of a sudden I was on the Johnny Carson show and all kinds of morning shows. The guys backstage would say, “Here comes our star.” And while we were on tour, I did all these interviews about opera. I was surprised by all this attention, but luckily it got quieter after a while.

H: How would you define the role of the prompter?

J: Prompting was fun and an adventure every night. I loved the intensity of it, staying focused, paying careful attention, trying to figure out what could go wrong next, watching out for singers who have insecure spots, keeping ensembles together. Prompters are like your mommy. Sherrill Milnes always said: “Joan, I look at you smiling at me and I breathe better.” Lots of people said that they knew I was there for them, they were not alone, and that it gave them confidence and they were doing better thanks to it. You put energy in your face and encourage them. We were in this together. I believe that you can initiate energy into other people. It takes a lot out of you, but it’s nice to know that I can do that and save something or help somebody who loses concentration or is not feeling well. One time, Dolora Zajick was on stage in Aida. Burning candles were about to set fire to her. I telephoned backstage and the stagehands came out dressed like soldiers and put out the fire with extinguishers. She was so focused that she didn't even notice anything. After the show, Dolora came to me and asked: “What was that noise during my aria?”

When you make a mistake, that's terrible. It's your responsibility to see that the singers get it right, so if you make a mistake yourself, it's heartbreaking for weeks. Singers were rarely mean if I made a mistake. Early in my career, I gave Marilyn Horne a cue that was two bars too soon. She told Clarice: “Your crazy friend brought me in too early.” But she was not mad at me and gave me a necklace I wear to this day.

I like the feeling of compatibility with the maestro. I have my eyes on him in the monitor, and I see where his muscles are, and my muscles have to be in the same place. You cannot have them in another place, whether you like it or not. I am his liaison with the singers, because there is such a great distance at the MET from the pit to the stage.

Fabulous conductors spill out ideas that you haven't thought of, which can add to your interpretation and to your perceptions. They might be looking for a sound or a rhythm that deepens one’s own interpretation. Carlos Kleiber was rehearsing Bohème at the MET, and we were warned not to talk to him because he was so important. Everyone was so in awe of him that they had the orchestra rehearsal in the pit. After a while he asked shyly why nobody was talking to him. He rehearsed a few moments of the opera and lingered on Mimi’s death chord. Once he got the result he was looking for, he taught them that every bit of the music was important: the pizzicato, the staccato, the legato. Everybody felt as if we were on holy ground, proud to be part of that production. For the rest of my life, I will carry that memory with me.

I was really fortunate to work with so many phenomenal conductors. As a coach at an opera house, you have the opportunity to sit by different conductors and see different ways of thinking, different solutions, different tempi.

H: Is there a “right tempo”? I complained to you once about a tempo that was too fast, and you said: “There is no one absolute tempo.”

J: I think that if you have a horse that weighs 300 pounds, it's not going to go as fast as a 200-pound horse. It just matters what you have within a certain confinement. If a tempo obstructs the meaning, or if it's done just for the flair of the conductor, then we're not going anywhere. The singer has to be comfortable; the singer has to breathe. The singer’s task is very physical, and if they don't have enough time to sing it, the tempo is wrong.

H: What about the “right voice” for a role?

J: There aren't exact parameters for who should sing what music, but we can look back to the list of past singers of a certain role. There's a place for everybody's voice, but singers cannot sing everything everywhere just because they feel like it. Singers should find roles in which they can be successful. If the suit doesn't fit, don't wear it. Voices in a production need to match and to be well balanced. The voice needs to be able to overcome the density of the orchestration. The venue will also determine what roles a singer can perform.

H: What about verismo repertoire? Operas that are based on historical events such as Fedora, Andrea Chenier, Adriana Lecouvreur, and ones like Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci, which focus on describing the lives of “regular” people.

J: I love the explosion of an emotion that is not as well-mannered as what we have had until then. It’s about guts and blood, much more visceral. People are not so hidden away and there are fewer filters. The women from the south of Italy who are betrayed by men from there explode their emotions, their vengeance. My grandfather came from an area outside Rome. This music sends me back to some of the people I remember from my childhood. I had a Sicilian fiancé at some point. Fire and temper and “you get off my land” kind of attitude. Actually, that kind of misunderstanding, as in Cavalleria, distresses me. But its visceral quality makes it exhilarating.

The characters are so interesting in operas like Fedora, Adriana Lecouvreur, etc. In Chenier, the most fragile moment is when Madelon brings her last surviving grandson to “donate” him to the cause of the revolution. It’s a way of binding our history to our music.

H: How is Puccini different for you?

J: Puccini combines humor and pathos, and he is such a master of the stage. He lets you laugh and then punches you in the stomach. If you think of La Bohème’s plot, he writes about the world following the French Revolution. These artists are poor because there are very few protégés of art remaining, now that the monarchy and the court are gone. Leoncavallo’s La Bohème shows it in even starker colors, in a fashion that is less smooth and “pretty.” Poverty, as well as the need for art and love, are recurring themes in many of Puccini’s operas. Think of Madama Butterfly, Tosca, Turandot, Il Tabarro, Gianni Schicchi, and La fanciulla del West. Puccini pays close attention to the words and to their poetic flavor, and likes to juxtapose funny moments, like “Musetta’s Waltz,” or the exchanges between the four Bohemians, with heart-wrenching scenes, like Mimi’s death. That is very Italian. You find that less in French music. But Puccini’s attraction for the French theater is also apparent, borrowing often from French plays and using French elements in his music. For example, the cut-off for words in Italian is usually very short and clean, whereas French has many words whose poetic pronunciation ends with a schwa vowel, which means that the ends are longer and more tapered off. When you look at Puccini’s musical notation for word endings, you often find a note tied to another short note, on the same vowel, for no obvious reason. I think he was trying to create an illusion of the French cadence of vowels tapering off. To me, that is a manifestation of his love for all French things. I have a respect for the plasticity of his vocal lines, as if he could not quite figure out what to do with the orchestra. Although, if one heeds the softer dynamics written for the orchestra every so often, then the music is much closer to the delicacy of French music.

H: What is the difference between working with an accomplished singer and an emerging talent?

J: Don't laugh. It is in the amount of gentleness. You can go straight to it with the professional. “Sweetheart, it's flat.” With a young talent you say, “Let's look at this intonation.” Because they can't sustain it emotionally.

H: You were surrounded by all these fabulous world-class singers. Why the interest in nurturing emerging singers?

J: I love what I do, and I am so lucky to be doing what I most love in this world. The programs for young emerging singers are a huge part of that. When I came into the business, the general attitude was one of not sharing information. Go figure it out by yourself. I wanted to change that. I thought that the opera world would benefit from passing on the knowledge. Coaches needed to be able to talk to each other without competition, in order to help singers. We're all on board together to make the production a success. If we don't share the information, it's lost forever.

When we went on tour to the Far East, we were asked to perform operas without recitatives, just the “musical numbers.” And we realized that they were missing the storytelling part of opera. We started thinking about educating audiences and the next generation of singers. A meeting with Paul Nadler in Israel (he won a conducting competition there), together with a few others who shared our vision, convinced us that we must help Israel revive its vocal scene. There was much investment there in instrumental music thanks to Isaac Stern, Itzhak Perlman, and many others, but the Israeli Opera of Edis de Philippe no longer existed. Placido Domingo told me what it was like when he was there, how he sang opera in seven different languages. But that was all gone. And the New Israeli Opera was just in its infancy. A meeting with the Mayor of Tel Aviv resulted in an adequate budget, which allowed us to include luminaries such as Renata Scotto, Alfredo Kraus, Sherrill Milnes, Nico Castel, Mignon Dunn, Renato Capecchi, Paolo Montarsolo, Martin Isepp, and hundreds more fabulous artists. I simply cannot name all of them here for lack of space and time, but it was a glorious group, the best of the best in every category, who shared our vision of passing on the knowledge to the next generations by bringing experienced artists to them. When you look at the current MET Music Staff, you find many members who were part of IVAI at some point.

In the first few years we had a very small group of Israeli singers, and mostly singers who came from abroad. The Israelis had very little access to the rest of the world at that time. Thirty years later, we are looking at two entire generations of Israeli singers, many of whom are having fine careers all over the world. And the list is not limited to singers. There are coaches, voice teachers, stage directors, conductors, and even one language coach. During my years at the MET, I came across so many of IVAI’s alumni, and it always gave me a sense of pride and joy. The concept of bringing the best artists, and mostly people from the field rather than teachers in a school, proved itself and became so successful that people started asking to have their own version of IVAI in their countries. That happened with Puerto Rico, Mexico, Japan, China, France, and Montreal, as well as a few cities in the U.S.

H: How did your book Complete Preparation – A Guide to Auditioning for Opera come about?

J: I was giving a series of master classes and my assistant at the time, Maria Ciaccia, taped them all and turned them into a book. It was also translated into Chinese.

Flipping through this fabulous book for the tenth time, I found many practical tips for the emerging young singer. The chapter and header names alone give an indication of your empathy and humor: “Hurry Slowly,” “Analyze, don’t criticize,” “Coping with rejection,” “Too much too soon.” There are some tips I remember from the first time I read the book, such as “The dress must enhance the person, but not upstage you or the audition,” “It’s one thing when you’re twenty to say ‘If my career only lasts twenty years, it is okay,’ but young singers don’t realize how soon forty comes and how much you may not want to give up singing at forty.” What is one message you would like to send to young singers nowadays?

Enjoy the process. Enjoy the studying, the growing, and the achievement. And to the rest of us, I say: It is so important to nurture and support young singers. It was the best thing I ever did!

H: Tell me what elements attract you to the music of Mozart, bel canto, Verdi.

J: Mozart’s music is so architecturally secure, with tempi that are always in their right element, not moving around too much, and without too much rubato in the middle of phrases. The music is glorious as it is put into melodies that fit the melancholy, the fun, the love. I adore Mozart’s daring to write wonderful relationships between men and women, in ridiculous and hilarious situations. The music is wonderful, the text is sparkling. Così, for example, is a miracle of understanding of the human spirit on so many levels, and I love that.

I fell into the bel canto “puddle” when Monserrat and Beverly Sills and several other magnificent singers were enjoying the flexibility and elasticity of that music, like a dress you can put on and make fit you. This music is so personal, and the text is so human and interesting. It represents an important part of our history and some of our nobler emotions. The fact that the orchestra does not have a complicated accompaniment underneath the singers allows them freedom of tempo and expression. In a later Verdi piece that is harder to do.

Verdi knew how to write stories. And he knew how to make the music fit the stories. The big elements he introduced were the importance and meaningfulness of rhythm and the

energy that he put into the rhythm. Verdi also plays with the combination of rhythm and tempo because the same rhythm in different tempi changes its nature. And he always attaches them to the right emotional field. Compare, for example, a few of the numbers in Rigoletto. The text leads the emotion, but the different rhythms and tempi indicate the mood immediately, even before the words appear: Questa o quella, the love duet; Cortigiani, Monterone’s second entrance; La donna è mobile; the quartet. Verdi also uses a “non energy,” if you will, when a character is listless or dreamy. Think of Violetta’s Dite alla giovine, as she agrees to give up Alfredo, or consider Gilda’s Caro nome, which starts hovering in the air and then picks up momentum as the aria advances.

Hemdi Kfir wishes to thank Lynn Warshow for her help in editing the interview

In 2022 the National Opera Association honored Joan Dornemann with a Lifetime Achievement Award. Much has been written about the first woman prompter of the Metropolitan Opera, one of the most highly respected opera coaches in the world. She worked at the MET for more than forty years as an Assistant Conductor, coaching singers like Luciano Pavarotti, Montserrat Caballé, José Carreras, Mirella Freni, Renata Scotto, Sherrill Milnes, Kiri Te Kanawa, Renée Fleming, Deborah Voigt, Neil Shicoff, Thomas Hampson, Juan Diego Flórez, and Anna Netrebko, among others. Many prominent American singers first met her when she was accompanying them in the semifinals of the MET Competition. She received an Emmy Award for her contribution to the “Live from the Met” broadcast of La Bohème starring Pavarotti and Scotto. In addition, she was a pioneer in the realm of summer programs for emerging singers as the Co-Founder and Artistic Director of the International Vocal Arts Institute (IVAI), which started in Israel in the late 1980s, with subsequent programs in Japan, China, France, Puerto Rico, Montreal, and numerous cities in the United States.

Hemdi Kfir, a language coach on the MET’s music staff, whose life changed thanks to her meeting Joan at IVAI in 1991, sat down for a conversation with her.